From Chaos to Order

I’ve done a variety of different things with computers and people during my career and developed the technical and leadership skills to identify and overcome technical and operational obstacles. Working on system administration, software and OS development as a developer and as management has given me a broader perspective and the ability to understand the position of other teams.

While most of my work in recent years has been remote I don’t work in isolation. I thrive on working with people at various levels and encourage each individual and team to contribute their best work toward a common goal.

I started my career doing Systems Programming on an IBM 360/65 at Clarkson College (now Clarkson University) in Potsdam, NY. Systems programming was what we called ystem administration those days. Instead of cool tools like Perl, Python and PowerShell, we had IBM 360 Assembly Language. Computers took up large rooms, and computing was done by submitting batch jobs (decks of punched cards) to the OS/MVT operating system and looking at the resulting printouts a while later. Definitely not environmentally friendly.

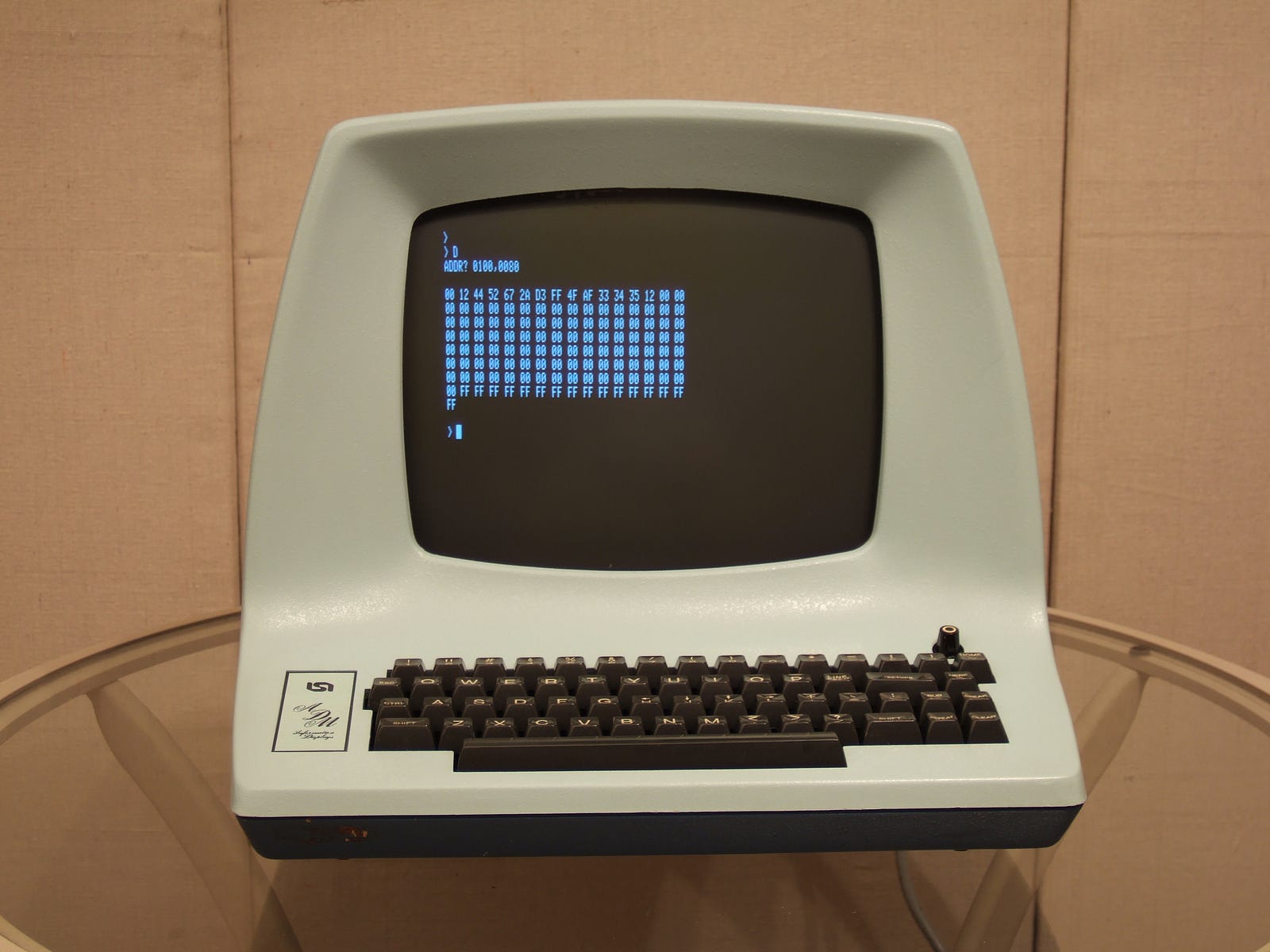

Time Sharing computing was the buzzword of the day. That’s where a mainframe would support many interactive users editing jobs to submit. This was done with the ROSCOE system, which was really just another batch job that never finished. It controlled a lab full of ADM-3A terminals, most of which were not equipped with lowercase chips. BACK THEN ALL CAPS WAS THE NORM AND WASN’T CONSIDERED SHOUTING.

Educational Resources Center

After I was at at Clarkson for a few years they built a new building combining information technologies, the library, media production and computing center into a new building on the hill campus called the Educational Resources Center. One of the goals was to bring innovative computing to the University.

As part of this move research was required into a new computing platform. The major contenders were the IBM 4341 and a UNIVAC 1100 series. The IBM 4341 won out, primarily because of the legacy administrative computing systems dependent on IBM software. In the long run this was a better decision, the IBM computing platform was supported for much longer than the UNIVAC.

The IBM 4341 supported virtual machines and ran VM/370, basically a hypervisor like today’s VMWare ESX. Under that we ran OS/VS1 to continue to process legacy batch jobs and provided more interactive computing via the McGill University System for Interactive Computing (MUSIC) a timesharing system written in FORTRAN and designed to run under VM/370.

My challenge was to get the basic VM/370 running and port our modifications to OS/MVT onto the newer OS/VS1 so that our administrative computing group to keep the college running. I spent many weeks alone in the new building to get the system running in time.

System Architecting

As my career at Clarkson progressed I became more involved in architecting solutions to computing challenges at the University. Some of these included:

Academic Computing

The engineering departments were not thrilled with the computing services on the mainframe. This is understandable as IBM’s main focus was business computing. I was part of a small team researching the options of a DEC VAX 11/780 or a Perkin Elmer computing system. The end result was the VAX 11/780 which, like the IBM, had better longevity.

Telecommunications Infrastructure

With the move of the computing center came the challenge of telecommunications and networking. The administrative computing group and most of the administrative offices which were the main users of the computing facilities were downtown and the computing resources they required were a mile away on the hill campus. These were the days before the adoption of the Internet so the options were limited.

Our solution was a dedicated cable link leased from the local cable company. On this link we were able to run 64k Baud synchronous lines and 19.2K Baud async lines. The 64K Baud sync lines worked fine for remote job entry (card readers and printers) and some expensive and proprietary IBM 3270 class terminals. The 19.2K async lines were not cost effective for remote terminal access though.

The solution we designed was an X.25 network that aggregated ASCII terminal connections onto the 64k Baud synchronous channels. This allowed the proliferation of ASCII terminals throughout campus at a lower cost.

I designed a physical telecommunications infrastructure that made it easy to maintain and debug all those synchronous and asynchronous telecommunications links. We had patch panels that allowed us to reroute connections quickly and also plug in to monitor them with a protocol analyzer. I spent many hours with said protocol analyzer diagnosing communications problems.

The PC era

Clarkson’s first foray into the PC was the Zenith Z-100 running the Z-DOS version of MS-DOS; the school became the first college in the nation to distribute machines to every incoming freshman in the Fall of 1983. It was very similar to, but slightly different from the IBM PC of the era. Everyone wanted one on their desk, however they also wanted to connect to the IBM 4341 mainframe and later the Gould super-minicomputer and the DEC 11/780.

My solution was to write a terminal program that allowed folks with PCs to connect into both the IBM 4341 mainframe and the new supermini-computer. Now folks with PCs could access the big computers without requiring a separate ASCII terminal.

That supermini-computer was my first experience with Unix. It was a Gould PowerNode 9080 running the BSD variant of Unix. Also making an appearance were the AT&T 3B2s and Sun Workstations.

The Internet

Another big thing in the 80s was networking. Clarkson first connected to BITNET, an educational network of mostly IBM mainframes. BITNET allowed e-mail and mailing lists as well as remote job submission. It even had support for instant messaging and functioned as an early social network. Our challenge with BITNET was connecting. BITNET required new members to buy a telecommunications line to an existing member. Because of the telecommunications tariffs it was cheaper to get a connection to a site outside of New York, so we ended up connecting to the University of Connecticut.

The next networking challenge was the fledgling Internet. I managed two connections to the Internet, one to the MILNET via a Mt Xinu BSD Unix system running on a DEC MicroVAX II and the other via NYSERnet which connected them to the wider world. Back then it was mostly e-mail and remote logins. Data transfer was via email and FTP and remote login used unencrypted telnet. This was well before the advent of World Wide Web.

Bringing up the Mt Xinu BSD Unix system was a challenge in itself. For example, I had ordered disks in sizes that were not yet supported by the OS. So during the installation I had to add a new entry for the disk size, recompile the kernel, and reboot. This went relatively smoothly and was a great learning experience for my first foray into Unix.

In those days of static host tables, before the domain name system, we needed tools to manage all the IP address assignments. I implemented an IP Address Management (IPAM) tool in our NOMAD database that let the operations staff handle requests for addresses and removed this responsibility from the programming team. This application generated host tables that were made available for download in various formats.

Cornell Theory Center

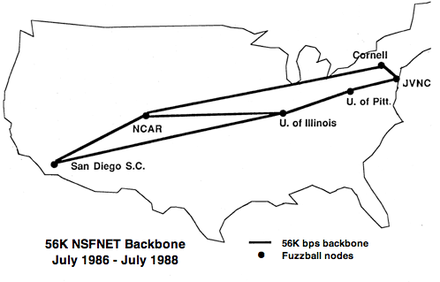

My experience with the Internet, Unix and software development landed me a job at the Cornell University Theory Center in Ithaca, NY to help run phase I of the NFSNET. There I became the lead programmer on the Gated project. Gated was an Open Source routing daemon used on the Unix hosts that formed the NSFNET and by several routing manufacturers.

When I took over Gated it was a hack to add the NSFNET HELLO routing protocol to the existing BSD routing daemon which supported only the RIP protocol. I turned it into a framework for efficiently implementing and testing routing protocols. When Cornell passed the project to Merit, Gated had support for RIP, OSPF, EGP, BGP, and Router Discovery.

During this time I learned some concepts that are still relevant today. I worked with a community of contributors to build a better project through collaboration. I also implemented a build farm with numerous different flavors of Unix and Linux on which I would spin up parallel builds to ensure the code changes compiled everywhere. I made heavy use of CVS for Source Configuration Management. To the chagrin of my management, the concept of Project Management was pretty foreign to me.

I also participated in the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) on the design of several routing protocols, including OSPF and RIP v2. Gated was an excellent platform for prototyping new routing protocols and had one of the first implementations of the BGP protocol.

This was the heyday of the Sun workstation and the beginning of BSD Unix and Linux running on PC hardware. In addition to extensive knowledge of TCP/IP networking, the protocols that are the foundation of the Internet, I learned a lot about BSD Unix, especially in the area of packet forwarding and routing tables.

When Cornell lost interest in the development of the Gated software, I accepted a job at Berkeley Software Design, Inc (BSDi). I had interacted with some of the principals at BSDi in my work on Gated and at the IETF and was quite interested in getting more involved in OS development.

BSDi sold and supported a commercial derivative of UC Berkeley’s BSD Unix called BSD/OS. BSD was a derivative of the original AT&T Unix as opposed to Linux which is a compatible re-implementation. BSD shares much of the same source code with the original AT&T Unix and there is much written on the AT&T lawsuit against BSDi and UC Berkeley.

Working remotely

As a company, BSDi was almost fully distributed, I worked from home and rarely met with my co-workers in person, usually at technical conferences. That does not mean I was isolated as we interacted daily via instant messaging, phone and e-mail.

Development was distributed as well. We all did our development on our local machines and would sync the changes up to the CVS trees at the main office. During my time there I worked on many different parts of the OS, from low-level interrupt handling though fixing and re-writing system utilities, improving the NFS and C library thread implementation and implementing locking in kernel networking subsystems.

BSDi was acquired by Wind River Systems, Inc, an embedded operating systems company whose primary product is VxWorks, a real-time OS. Wind River realized that they needed to expand their portfolio with a general purpose embedded Operating System. The BSD/OS project lived on for a while as the Platform for Server Appliances, but failed to gain traction against the juggernaut that is Linux.

Linux

Eventually Wind River changed direction and embraced Linux and my involvement turned to management. This transition occurred because my boss at the time noticed that instead of staying heads-down, I would keep in touch with my co-workers, even calling them up on a phone to actually talk. This transition was nothing like that in the recent Dilbert story arc.

Board Support Packages

One of my first responsibilities on the Wind River Linux team was managing ports of Wind River Linux to new boards, this was referred to as developing a Board Support Package (BSP). There was a lot of miscommunications about what this meant and the prerequisites developing a BSP. I worked with my team, Product Marketing, Alliances and other teams to come up with a process for BSP development that was explicit about prerequisites and deliveries. Years later when I had moved on to managing other parts of Wind River Linux this process was still in use.

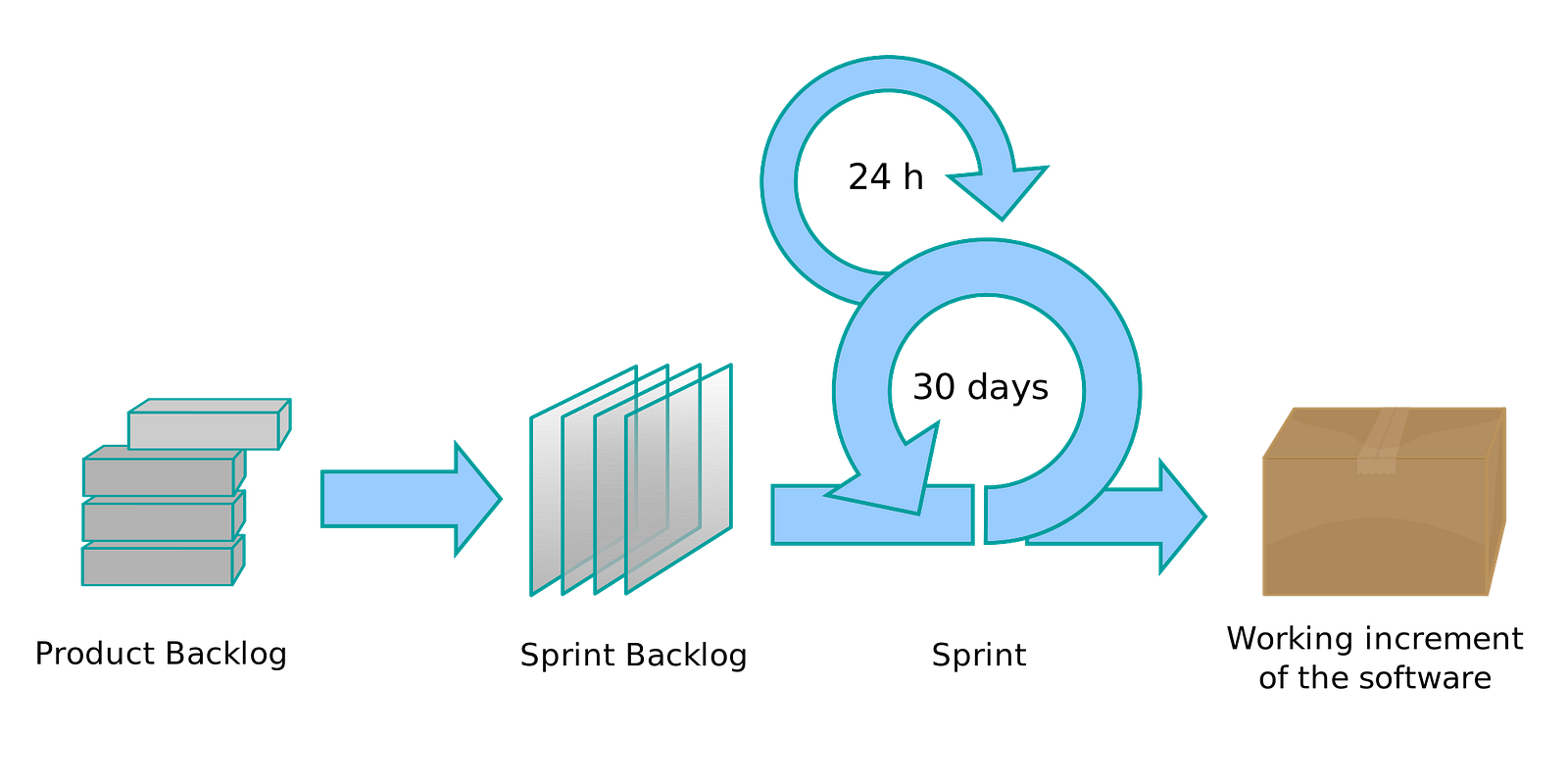

Agile

As an Engineering Manager I learned to dislike the Waterfall model of Project Management. The up-front planning of the Waterfall model does not adapt well to complicated software projects. The Wind River Linux team was one of the first to embrace the Agile model of Project Management. I helped lead our transition and we managed to apply it quite effectively despite having widely distributed teams. When I left Wind River I was managing a few Agile teams as well as the roll-up of all the Wind River Linux Agile teams.

ISO 9001

One of Wind River’s major customers requested Linux meet ISO 9001 specifications. Put simply, ISO 9001 requires you to document what you are going to do, document that you have done it, and continuously improve your processes. While initially scary, this is a good thing and something that Wind River Linux was already doing to a large extent. The challenge here was not to add more process than was actually needed, ISO 9001 does not need to be heavy-weight. I left before we had been fully audited but a preliminary audit was successful.

Technical Chops

While doing management I kept my technical skills up to date, solving technical problems with development and engineering operations. During critical times I would jump in to fix bugs. I especially enjoyed projects where my technical chops could be applied. One way I did this was by building a Linux Infrastructure group to efficiently support the Wind River Linux development, test and release efforts. Our small team (basically less than one full-time person) managed 150 systems in three data centers (Beijing China, Oakland California and Ottawa Canada) using Docker Containers to do thousands of Wind River Linux builds a day.

Git-based installation

A big challenge with Wind River Linux was the installation experience. Wind River Linux is a source distribution used to create a Linux Distribution to deploy to a customer’s board. It is similar in size and functionality to the SDK development platforms like Android Studio and Apple’s Xcode. Wind River’s standard installation technologies were not designed with the Wind River Linux model of hundreds of git trees.

I led the project to convert Wind River Linux to a git-based installation model from a management perspective and also made significant technical contributions. This was a complicated project which required coordination with several other groups at Wind River with different priorities. Our git-based installation needed to work seamlessly with the standard Wind River Linux Java-based installer as well as stand-alone. We had to work closely with the Release Engineering team responsible for the web hosting. While frustrating at times I enjoyed working with all these groups to overcome the issues and release a solid product.

Engineering Management

While spearheading these side projects I was also first-line manager for a team of about ten software developers, including two architects. I directly managed the development of the Wind River Linux build system and system integration as well as the integration of the compiler toolchain supplied from outside the Wind River Linux group. I also had day-to-day responsibility over the half-dozen teams delivering all the components for a major Wind River Linux release. This included coordination with Product Management, Release Engineering, Export, Intellectual Property, Documentation, Installation, IDE development, Customer Support, and Field Engineering.

Leaving Wind River

Wind River decided to focus more on co-located development in Centers of Excellence and slowly let go of most remote folks. My turn came in the summer of 2016.

In May of 2017 I joined AppNexus, Inc as a Senior Systems Architect supporting disagregated storage in our private cloud. Configuration Management with puppet and scripting with python and REST APIs were supplemented by a central SQL configuration database.

In 2018 AT&T acquired AppNexus and merged it with AdCo to form Xandr.

In December 2021, Microsoft announced its intention to acquire Xandr from AT&T. This acquisition was completed in June of 2022.

At the end of June, 2025 I retired from Microsoft.

While I was not working during the summer of 2016, I formed Scobey-Carvell an LLC that I can use for consulting.

I’m always willing to consider work.